There seem to be two phases to living in a different culture. Phase I is essentially the "outsider" phase in which one feels like one is completely removed from the culture in which he or she is living in, an observer looking through a glass pane in a museum. Everything about the culture seems radically different, from the way people interact, to the conditions in which they live their lives, to their everyday habits. For me, at least, a sense of "other-izing" occurs, in which all people of a different culture are lumped together as somehow different from me yet nearly identical to each other.

In Phase II, all that reverses. One begins to see past the superficial differences between cultures and realizes that one was only viewing things through a filtered lens. The outward differences are no longer so pronounced as one comes to understand that there are many elements of this new society which closely resemble one's own- from intergenerational conflict to community events. Even the once seemingly homogenous people of the new culture become strikingly different from one another as distinct personalities emerge- there are selfless, good-natured people, but also womanizers, misanthropes, and connivers.

It was in my last few weeks in Ethiopia that I began to more fully embrace Phase II, spurred on, no doubt, by the weekends I spent with my local friends in the community.

Watching the local soccer games came to be one of my regular weekend pasttimes. Though these were casual games played by the residents of Dembi Dollo, the level of competition surpassed the average pick-up soccer game held in the US. The fact that a large crowd of local kids and many adults came out to the games and would often rush the field and perform victory dances after a goal only added to the excitement. In fact, the weekly games struck as me as analogous to a weekend little league game or high school football game in that they were simultaneously sporting events as well as events which brought the community together.

One of the characters I met during one of these soccer games was two-year old Robera, son of my Ethiopian friend Gabayo.

Robera was a two foot tall agent of chaos, delighting in pushing chairs over, stuffing sand in his shoes, and running anywhere his two small legs could carry him. He might have been insufferable if not for the fact that he radiated infectious joy in everything he did, and he generally left a smile on the faces of all those in his presence.

One of Robera's companions was one year old Wabi, the son of Sister Evelyn's driver. Without fail, Wabi would begin bawling everytime he saw me. I guess I should've worked on looking less scary.

Wabi crying because he saw me

Apparently I succeeded in shedding my intimidating demeanor over the next few weeks as the kids who had previously only stared at me from afar began to approach and sit next to me. A few kids even reached out to touch me- my face, arms, boots- apparently intrigued by this foreigner who looked so different from the Ethiopians they were used to.

One Saturday, the local youth association put on a performance featuring skits, sermons by local pastors, comedic roasts, and short talks by members of the community. In one skit, the town bully was humiliated when a robber who attacked him turned out to be a little girl in disguise while in another, a smoking womanizer realized the errors of his ways and became a pastor.

The pastors addressed a number of topics, from the trappings of materialism and wanting luxuries such as nice cars, to the ways in which technology such as Facebook can be both beneficial and detrimental to our spiritual lives. I was struck by how prescient these sermons seemed, as they very well could have been delivered to a church youth group in the US with little modification. The slapstick humor in the day's skits and the lighthearted jabs during the roast also resonated surprisingly well with my American-developed sense of humor.

costumed students before the performance

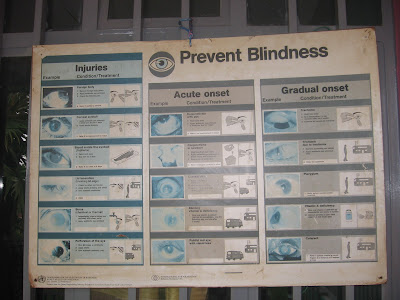

On my last day at the eye clinic, the clinic staff hosted a farewell dinner, complete with the requisite injeera, meat, and coffee. As bittersweet as it was to be leaving my friends and coworkers of the past two months, I was thankful for the impact they had had on me- from lessons in ophthalmology to their warmth and generosity to instruction in Ethiopian culture and the Oromo language.

about to eat nashif- minced lamb and garlic between two sheets of injeera (the word nashif means "good")

farewell dinner

receiving a traditional Ethiopian shirt as a thank-you gift from Mitiku on behalf of the eye clinic

Ethiopian assimilation complete!